History & Mission

The CARE Consortium endeavors to provide necessary infrastructure and scientific expertise to study concussion.

“The work and research of the CARE Consortium will make a lasting impact on sports and military medicine and on how we approach, diagnose, treat and prevent concussions. By leveraging multiple sites, sports and athletes on a nationwide scale, we can collect convincing data to change the way the public views and understands brain injury.”

-Thomas McAllister, MD

Established in 2014, the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) and the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) funded the Concussion Assessment, Research and Education (CARE) Consortium to inform science, clinical care and public policy related to concussion and repetitive head impact exposure (HIE) in U.S. Military Service Academy (MSA) cadets and collegiate student-athletes.

To date, CARE has enrolled >50,000 MSA cadets/midshipmen and NCAA student-athletes from 30 participating collegiate institutions, representing 26 NCAA sports, and military training and other recreational activities. In addition, the CARE study has captured data on over 5,000 concussed cadets/midshipmen and athletes – the largest concussion database of its kind.

From the outset, this public-private study was designed to answer key knowledge gaps around clinical and neurobiological recovery, brain structure and function, and factors predicting outcomes in MSA members and NCAA student-athletes.

- The initial phase of CARE (“CARE 1.0”, 2014-2018) focused on the short-term outcomes (i.e. six-months) following concussion.

- The second phase of the study (“CARE 2.0”, 2018-2021) investigated the effects of sport, military training, and concussion over the course of a collegiate career and outcomes up to five years after graduation

- The third phase of CARE is known as the CARE/SALTOS Integrated (CSI) Study, or CARE/Service Academy Longitudinal mTBI Outcomes Study Integrated. This phase will investigate the nature and causes of long-term effects of head impact exposure and concussion/mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) in former NCAA student-athletes and military service members.

- The CSI project will build upon existing CARE/SALTOS research by following former CARE participants beyond graduation to evaluate the long-term or late effects of HIE and/or concussion/mTBI for over 10 years or more after initial injury or exposure.

The CARE data collected to date represents the most diverse concussion data of its type ever collected and allows for analysis of groups often neglected in the medical literature. The CARE data set is diverse in terms of race (36% non-white), gender (40% female), and levels of head impact exposure from participants in contact sports, limited-contact sports, non-contact sports, and military service academy members. It is also the first major concussion study to assess both women and men in 24 sports; prior to CARE, most concussion literature came from men’s football and men’s ice hockey.

The CARE Consortium has published more than 90 scientific papers and has been influential in improving sport participation for athletes of all ages.

Key findings thus far include:

Work from the Concussion Assessment, Research and Education (CARE) Consortium continues to shed light on the natural history and neurobiology of concussion and repetitive head impact exposure among collegiate athletes and military service academy cadets/midshipmen. Many of the key findings to date are helping to inform decision making around mechanisms of concussion, mitigation of concussion risk, and refinement of concussion management. Some key examples are highlighted below.

CAUSES OF CONCUSSION:

concussion was assumed to be caused by a single, large magnitude head impact.

that concussion risk is associated with (1) the magnitude of a single impact; (2) the individual’s recent cumulative head impact exposure prior to injury; and/or (3) individual concussion susceptibility thresholds (Stemper et al. 2019; Rowson et al. 2018). Furthermore, increased head impact exposure in football preseason is associated with an increased risk of concussion during the regular season (Stemper et al., in press, accepted for publication).

MITIGATION OF CONCUSSION RISK:

the frequency and implications of delayed reporting of concussion symptoms was not known.

that two-thirds of individuals delay concussion symptom reporting, and this delay is associated with up to a three-day delay in return to play (Asken et al. 2018). Awareness of these findings should facilitate improved methods for recognition and diagnosis of concussion in athletes in whom a “smoking gun” impact was not immediately identified and/or signs and symptoms of concussion are not immediately evident.

the contribution of different components of head impact exposure (e.g. Spring Football vs. Preseason Football vs. Regular Season football) to concussion was not known.

that preseason football accounts for a disproportionate incidence of both concussion and head impact exposure. Although preseason training camp accounts for only about 20% of the fall football season, it accounts for nearly 50% of all concussions and head impact exposure twice the proportion of the regular season. (McCrea et al. 2021) In addition, CARE data show that nearly 3 in 4 concussions and 70% of all head impacts occur during football practice, not in games. (McCrea et al. 2021). Furthermore, the profile of head impact exposure and number of concussions associated with Spring Football is nearly identical to the preseason. These findings have led to reconsideration of practice guidelines for both Spring and Preseason Football (Stemper et al. 2020).

REFINEMENT OF CONCUSSION MANAGEMENT:

the normal (mean/median) return to activity time following concussion was considered to take approximately 1-2 weeks.

that ‘normal’ recovery may take up to one month for the majority (80%) of participants (Broglio et al., 2021). Clinical practice in concussion management and return to play has also changed dramatically over the past 20 years, which results in a significant reduction in risk of repeat concussion. (McCrea et al., 2019).

while each successive concussion was associated with longer recovery time in some individuals, the data were focused almost exclusively on male football athletes.

that athletes with 3 or more prior concussions experience longer recovery times and increased burden of post-concussive and psychological health symptoms years after injury in a variety of collegiate varsity sports (Broglio et al., 2021).

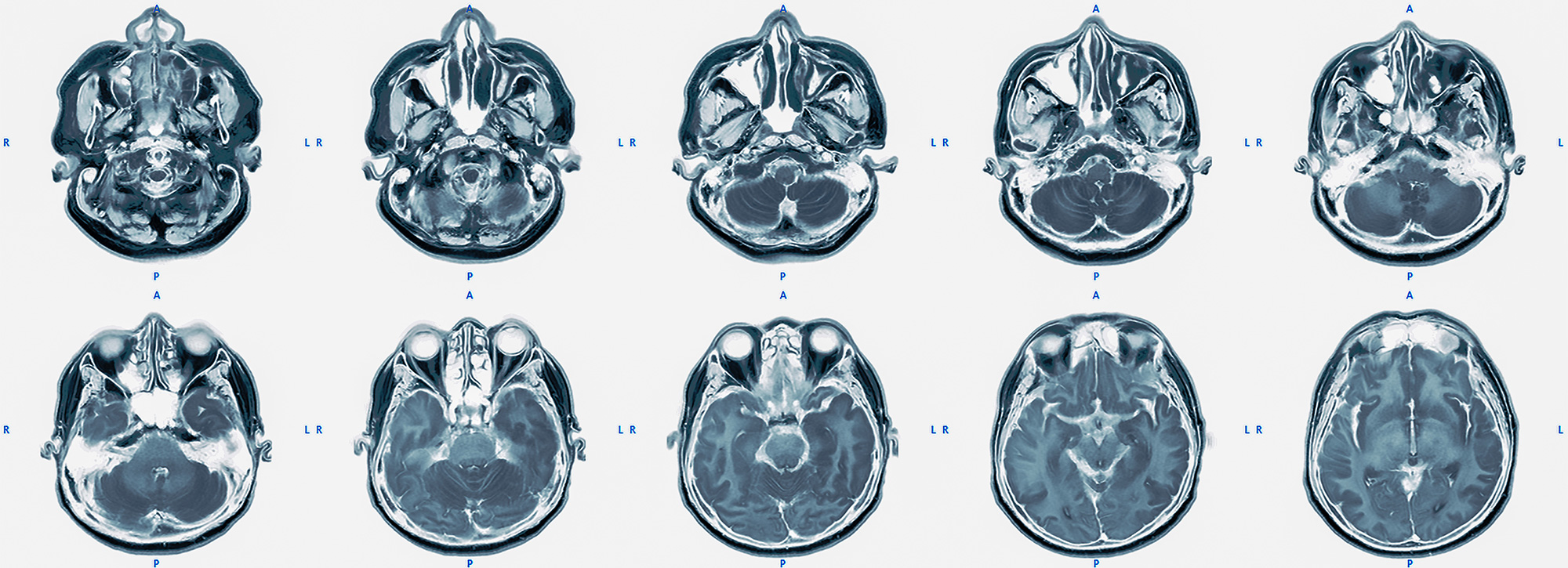

concussed athletes were highly unlikely to have abnormalities on conventional brain imaging.

that advanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of brain structure and function distinguishes concussed athletes from contact and non-contact controls without concussion. Importantly, these differences correlate with clinical symptom severity and predict time to recovery and return to activity after injury (Mustafi et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2019; Meier et al. 2019; Wu et al. 2020).

resolution of concussive symptoms and ability to tolerate vigorous physical activity were considered reliable indicators of full recovery.

that differences in neuroimaging and proteomic biomarkers can persist beyond clinical “recovery” (Wu et al. 2020; McCrea et al. 2020).

there was limited data on how sport-related concussion affects elevation in blood protein biomarkers.

that acute concussion is associated with increased levels of select biomarkers (GFAP and UCHL-1), with some evidence of a “dose-response” relationship, where greater biomarker elevations are observed in more severe grades of concussion (McCrea et al. 2020; Giza et al. 2021). Furthermore, the level of plasma biomarker elevation is associated with some indicators of speed of recovery and return to play (Pattinson et al. 2020).

the impact of modern concussion management practices on athlete safety was not known.

that widespread implementation of modern concussion management practices (symptom free waiting period/graded exertion protocol), are associated with reduced risk of repeat concussion (McCrea et al. 2019).

Original Participating Sites

When CARE 1.0 began in 2014, 30 sites participated in data collection on student athletes and military cadets/midshipmen. These sites continued their hard work through the end of CARE 2.0 in 2021. CARE leadership is grateful for the contribution all of these individuals gave. See a complete list of CARE Site investigators and researchers past and present.